In recent correspondence with a science writer, I was asked a few questions about my work with Moira Jardine, A Plasma Torus Around a Young Low-Mass Star (link). I spent some time crafting my response and I thought it’d be worth sharing.

1) What is a plasma torus? I understand it is a doughnut-shaped structure of plasma, but I’d like to be able to cite you.

A plasma torus is a ring of ionized gas held in place around a planet or star by its magnetic field. These “rings” can be shaped like doughnuts; they can also be warped, twisted, and pinched. The difference from other types of plasma condensations (such as Solar prominences) is that plasma tori are long-lived and distributed in longitude. One example is the ring of plasma that exists around Jupiter, which is fed by Io. Another example exists around the star σ Orionis E, a bright blue star just next to Orion’s belt, which is fed by the star’s wind and supported by its rotation and magnetic field. Our article is about a red dwarf star that shows new evidence for a similar structure.

2) Could you describe the circumstances that led you to spotting the torus? Was it an accidental discovery?

We’ve known for a decade now that a small fraction of young red dwarfs show complex variations in their brightnesses that repeat with periods of hours to days. Two possible explanations are either that transiting opaque material corotates with the star, or that the surface of the star itself is covered in dark starspots in a complex geometry. I call these mystery stars “complex periodic variables”. The early discoveries of these objects were led by Luisa Rebull and John Stauffer using NASA’s K2 mission. I was inspired by their work to use NASA’s TESS mission to find many more. However neither K2 nor TESS is capable of ruling between the origin stories of circumstellar material vs. a complex distribution of starspots.

One possible approach for distinguishing the models is to make a spectroscopic movie. If you measure a star’s spectrum as something passes in front of it you can learn about the occulting material. That was my hope – to try and see whether the spectra would show us anything about material around the star, or whether they could be explained with only starspots. These were the first time-series spectroscopy observations for a complex periodic variable star.

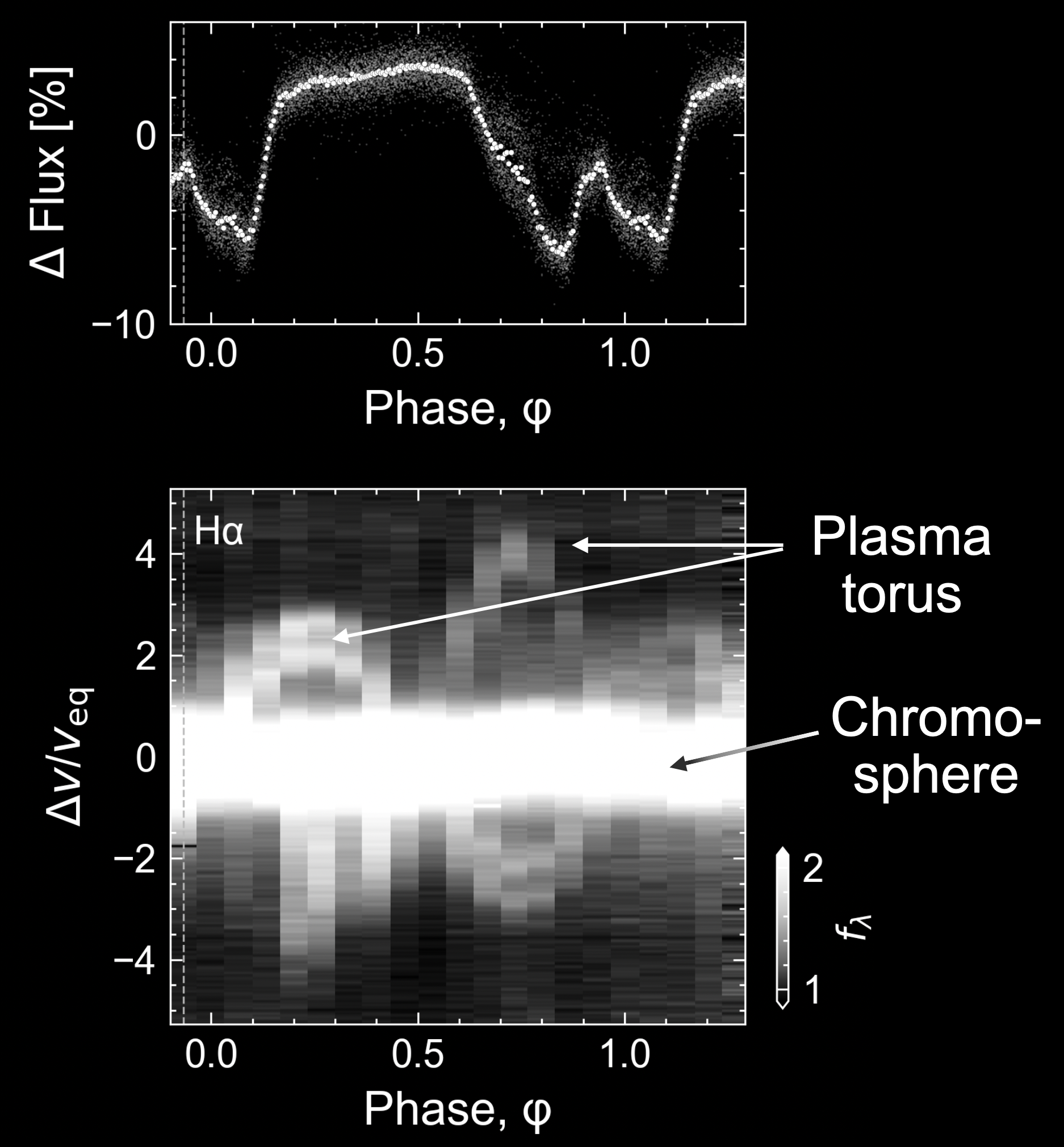

What we found was better than expected, so in a sense it was accidental. The serendipitous surprise here is that the spectra show circumstellar material emitting at specific wavelengths. In particular, Figure 3 of the paper (panels b or e) show the main discovery: there are two regions around the star that emit in Hα light (the hydrogen 3->2 transition). So, the direct interpretation is that there are two patches of plasma on either side of the star, that co-rotate in lockstep with the rotation of the star’s “surface”.

Emission from plasma clumps orbiting TIC141146667. See the paper for full description. Top: TESS light curve, Bottom: Keck/HIRES spectra.

3) You mention that two patches of plasma were found on either side of TIC 141146667. What led you to conclude that they constitute a torus encircling the star?

The spectra, which are sensitive only to hydrogen gas, show that there are two blobs of plasma on opposite sides of the star that rotate with it. This statement doesn’t depend on models.

The interpretation that these blobs are the densest parts of a warped plasma torus comes from models that predict what the spectroscopic and photometric features of such structures would be. A few such models are below - these movies were made by Richard Townsend and are shown here with permission.

Richard’s model shows that if a rapidly-rotating star has a dipolar magnetic field (red arrow) tilted with respect to its spin axis (yellow arrow), it can sustain a warped torus of plasma. This model predicts: i) sinusoidal-in-time Hα variability, ii) double-peaked Hα emission when viewed at specific rotation phases, and iii) W-shaped broadband photometric eclipses when the dense regions pass in front of the star. We see all three features in our data, which is what led to our conclusion that the light curves and spectra of our star are best explained by a warped plasma torus.

4) What is the significance of the torus? Also, you mention that 10% of M-dwarfs, the stars most likely to harbour Earth-like planets, have such tori; would their presence extend or reduce the habitable zone?

The average M dwarf does indeed appear to host at least one rocky planet, near Earth in size. This statement applies within orbital periods of 100 days. However most known M dwarf planets are far too hot to host oceans or atmospheres. Even the ones that might be capable of having water on their surfaces may not be hospitable. This is because the stars begin their lives very luminous, and decrease in luminosity over the first few hundred million years – so the M dwarf planets could become desiccated. Young M dwarfs also emit intense bursts of UV, x-rays, and energetic particles, which could erode the planetary atmospheres and sterilize the surfaces.

What we’ve seen suggests that one of these mystery variable stars, complex periodic variables, has a warped plasma torus. Since it was the first one for which this kind of data have been acquired, this suggests (though it remains to be proven!) that similar structures may be present around all complex periodic variables.

Although we don’t know what fraction of young red dwarfs have spectra like what we saw, we do know what fraction of young red dwarfs are complex periodic variables. It’s 3% at t=1 million years, and it decreases to 0.3% at t=100 million years. However to see the “complex” photometric features, we need to be viewing the stars edge-on, just like to see a transiting planet you need to see it edge-on. If you account for this geometry, then these observed fractions are compatible with at least 10% of M dwarfs hosting these types of warped plasma tori early in their lives. A smaller total fraction of M dwarfs, perhaps a few percent, seem to sustain their tori for up to one hundred million years.

It is not clear whether these tori are connected to habitability. While it’s possible that a planet could exist near or even inside a torus (just like Io exists within its torus!), there is currently no direct evidence for this scenario. If such planets did exist, they would be much too close to the star to host water on their surfaces.

The broader significance will depend on where the material in the torus comes from. It could come from the star; it could also come from external sources, like an undetected natal disk, or an undetected planet. Future work will have to figure that out. For the time being, I’m just glad that we are learning that such structures are there in the first place.